|

Covering the entire range of combatants of the past one hundred years,

across boundaries of culture, geography and time, this project is

meant as a polyphony of voices revealing how people find themselves

in war, what happens to them there, and the marks that remain when

the fighting is over.

If I discovered any single universal truth about war in the years

of this book’s gestation, it is that it is a deeply personal

experience. This is reflected in the many roads that people take to

get there. While generally young and disadvantaged, the men, women

and children who fight on the frontlines hail from all walks of life.

Conscripts and volunteers, patriots and rebels, those lured by adventure,

and those bound by a sense of duty.

What

is common to all is the aftermath. Here, one culture mirrors

another. It makes no difference if one has been in a "bad"

war or a "good" war, justified or unjustified, on

the winning or losing side. As Elvigio Pellitero, who fought

in the Nationalist army under General Franco during the Spanish

Civil War, said: “We were ignorant. We thought we would

probably die, that’s all. We fought, we won. If we had

lost it would have been just the same.”

During a visit to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington

D.C in 1991, I noticed children looking at the veterans there

with an odd curiosity. Indeed, there was something inherently

different about them. Civilian visitors are perhaps daunted

by the number of names on the Wall and angered or saddened by

what happened in Vietnam. But the veterans visiting the site

are not removed from the experience. They carry war with them

day to day. They’ve been responsible for death, and faced

their own. There is an aura around them, an aura born of having

witnessed something that should never be seen. It was this I

wanted to capture. I wanted to get past the macabre curiosity,

which I too had, and to move through the fear and horror of

seeing them with a missing limb or a burnt face—to see

veterans beyond their wounds, but to capture the war in their

wounds and through their memories. |

WWII vet in Bénin |

1991

© Lori Grinker |

|

The question of which conflicts can truly be called a “war”

came up numerous times during the course of this work. The Vietnam

War was never declared a war, nor was the Korean War or the Algerian

War of Independence. Officially, “the Troubles” in Northern

Ireland are not a "war," and neither is the Palestinian

Intifada. When asked about this, ex-combatants all responded the same

way: “We bleed the same blood, we kill and die with the same

bombs and bullets whether you call it a conflict or an insurrection,

whether it’s been officially declared war or not. What’s

the difference?”

Over the past fifteen years this project was supported through publication

in magazines, several generous grants, and the guidance of my agency,

Contact Press Images. When the time came to turn Afterwar into a book,

Contact’s director, Robert Pledge, who had been involved since

the inception of the project, and I sat down and discussed the layout.

Ultimately it was decided to organize the book in reverse chronological

order, from the most recently ended conflicts, reaching back in history

to the early part of the century. Reverse order is a way to peel back

the layers of time, a way of tracing the mad route of the past century

back towards its origins.

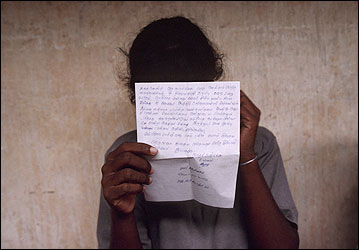

Sri

Lanka Civil War veteran |

1999

© Lori Grinker |

|

While

working in some thirty countries during the course of this work,

in addition to research and planning, I followed to some extent

a more poetic impulse, trusting the accidents of fate that led

me to my subjects. It was never my intention to create an encyclopedia

of war.

Each chapter contains a small section of data, including numbers

of casualties for each conflict in the book. Whenever possible,

I listed both the number of killed and wounded. Where extreme

discrepancies in the figures appeared in a variety of sources,

I’ve included a range of numbers. |

A final issue of historical authenticity inevitably came up in the

matter of names used in this book, of both the wars and their combatants.

Wars often have several names, depending on which country writes the

history. “The Vietnam War” to Americans is “The American

War” to the Vietnamese. To resolve this dilemma, in the book’s

timeline, wars are listed by the most commonly used name in addition

to the name used by the participants themselves. If adults gave permission

to use their full names, they have been included as such. In order

to protect the children included in these pages only their first names

have been used.

The past century was one of history's deadliest. More than one hundred

million people died in over one hundred and fifty conflicts. Countless

others were wounded as nationalism, competing ideologies and religions,

and genocidal conflicts raged across Europe, through Asia, Africa

and the Americas. There is no reason to believe it will end anytime

soon. Those sent to war are cannon fodder, and we live vicariously

through their violent experience. We watch the reports from the front

on television as if it were a spectator sport. But they suffer for

us. They are our sacrificial lambs. I hope their images and words

will serve as a powerful reminder of the wastefulness of war.

|

Lori

Grinker

New York City, April 2004

From Afterwar: Veterans From a World in Conflict by

Lori Grinker

(de.MO 2004) |

|

|